September 2, 2021

Three Wyoming Valley Levee gaps have been permanently closed, eliminating the need for a cumbersome temporary flood gate and sandbags when the Susquehanna River rises.

Due to the opening’s size, sandbags were not feasible. Instead, a levee crew of four or more had to spend a full day installing a mix of support posts, braces and aluminum logs to close it off, he said.

“It’s really going to improve our flood-fighting efficiency. Think of all the resources we had to deploy before,” said Christopher Belleman, executive director of the Luzerne County Flood Protection Authority that oversees the levee system.

Belleman expressed his relief while recently checking out the three now-filled gaps with authority project engineer Michaela Fehn.

The largest, known as the Swetland Lane closure in Wyoming, was approximately 39 feet wide and 11 feet high and flanked by two graffiti-covered concrete walls.

It dated back to the original 1940 levee construction to accommodate rail lines that are now inactive and owned by the county Redevelopment Authority, Belleman said.

Due to the opening’s size, sandbags were not feasible. Instead, a levee crew of four or more had to spend a full day installing a mix of support posts, braces and aluminum logs to close it off, he said.

It is now a grass-covered wall that blends in with the rest of the earthen levee and includes a new access ramp in case a rails-to-trails system is eventually added in that area, Belleman said.

Fehn said she spent extensive time working with the project contractor — Jessup, Pennsylvania-based Fabcor Inc. — to ensure the compacted clay used to fill the opening was the right consistency and not too watery.

“It is crucial that they get it right,” Belleman said.

The second closure off Shoemaker Avenue in West Wyoming had required 725 sandbags, Belleman said. It was only 2 feet high but ran a length of about 34 feet, he said.

Grass already is taking atop the addition. As with the Wyoming opening, this one had dated back to the levee construction for trains that once passed through.

A driveway also was added to access this site so maintenance and inspection crews won’t have to enter through an adjacent cemetery, Belleman said.

At the remaining finished closure on Railroad Street in Plymouth, nearly 1,000 sandbags will no longer be needed to fill a 3-foot-high and 26-foot-wide opening.

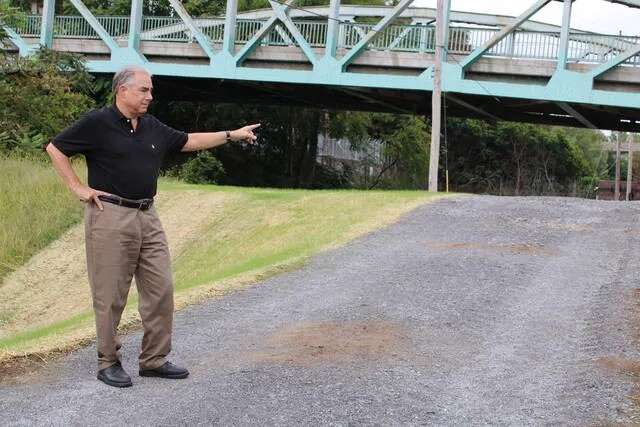

The street cut through this spot for access to a private utility substation. This portion is now level with the earthen wall. A gravel cover was added so the substation can still be reached, but Belleman said the stone will be removed and replaced with grass if the utility proceeds with plans to relocate the substation.

Standing atop the spot with the Bridge Street Bridge behind him, Belleman gestured at the properties below that benefit from this project.

Four more closures are pending as part of the $934,930 project, which will be primarily covered by a grant the Federal Emergency Management Agency awarded last year.

On Beade Street in Plymouth, the authority is awaiting final approval of a Pennsylvania Department of Transportation highway occupancy permit needed to slightly increase the street’s grade so it crosses at the height of the levee, Belleman said. About 1,500 sandbags are needed there.

The three other gaps in Edwardsville, Wilkes-Barre and Exeter can’t be eliminated because they are needed for access, Belleman said.

The Edwardsville opening and another on the opposite side of the Black Diamond Bridge in Wilkes-Barre must remain passable for still-active Norfolk Southern Railway train traffic.

To end reliance on sandbags, the project will create “stop log” system of aluminum beams at both rail openings that can be quickly set up and dismantled by a two-person crew as needed.

The authority is working with Norfolk Southern on a final construction agreement, he said.

The final opening on Wilkern Street in Exeter must remain to provide access to a cemetery and some other properties, Belleman said. A sliding gate will be installed so sandbags are not needed there.

In all, Belleman estimates the seven projects will eliminate the need for more than 7,000 sandbags.